When a beloved musician gets “canceled,” we as listeners are forced to make a choice: stop listening, or reconcile our continued support of the artist with our supposed values. Cancel culture is closely associated with the #MeToo Movement, which brought multiple high profile predators to justice after decades of unchecked abuse. Unfortunately, “cancellation,” as a concept, is resolute – it leaves little room for nuance. It has devolved into near-constant surveillance of one another for lapses in moral judgment that warrant retribution and public shaming. As a result, cancel culture gives people reason to fear that listening to problematic musicians makes us complicit in their ethical wrongdoing – particularly if they are alive to collect royalties.

Though the industry may see musical artwork as a product to be sold and promoted, it holds unique aesthetic value and meaning to listeners, and our varied experiences with art belong to us. When we devote time to the aesthetic experience of music, it can inspire some of the most transcendent moments in our lives. It can make us feel seen and heard; it can make us forget ourselves and remember exactly who we are, all at the same time. Whether or not people share the same musical preferences, for most, music is also linked to autobiographical memories that evoke nostalgia. Having positive memories and associations with music hardly warrants apology. It is a joy we should readily permit ourselves.

Cancel Culture is Binary

I understand why it's suspicious when folks outright condemn “cancel culture,” “political correctness,” or “wokeness.” It’s easy to wonder if they also preface offensive jokes with “I like dark humor,” or if they sympathize with perpetrators of sexual assault rather than their victims. Whatever their problematic pleasure may be... the most vocal critics of cancel culture seem to enjoy saying or doing insensitive things. For those of us who generally try to behave like conscientious adults, "cancellation" may seem fair, like justice and accountability for wrongdoing. After all, cancel culture is well-intended, at its core – "do bad things, and suffer the consequences." That being said, most of us also forgive friends, family, coworkers for getting it wrong sometimes. If we care about people, we generally seek to understand them and to help them when they make mistakes. Meanwhile, famous musicians can be retroactively called out or canceled for mistakes they made as children. If average people were under the same scrutiny, we might also get cancelled for things we said or did as pre-teens, trying to impress our friends with jokes that maybe we didn't even understand. Perhaps we don't empathize with celebrities the same way because we forget that they are people, too. They make mistakes, too. If cancel culture considers any person a lost cause based on childhood behavior, it is a moral code which requires further examination.

At its worst, cancel culture doesn't just come for musicians themselves. Participants in cancel culture often adopt an attitude of moral superiority and criticize listeners as well. To help listeners make informed choices, Revex Productions assembled a Big List of Problematic Songs and Artists, which includes Elvis Presley, Iggy Pop, Nick Cave, Red Hot Chili Peppers, among others. A disclaimer above the list reads:

"That you or I like someone is not a valid reason for them to not be on this list. It’s a binary thing, they did something problematic or they didn’t. Minor transgressions are on the list, even if apologized for or forgiven."

The disclaimer highlights one of the main failings of cancel culture: it is binary. Cancel culture says we are either right or wrong; we are either righteous or problematic. This conception of morality leaves no room for making mistakes. However, enforcers of cancel culture are often guilty of fundamental attribution error, wherein we attribute other people's mistakes to their character as a whole, but when we ourselves make mistakes, we consider the circumstantial factors which informed them. For example, a proponent of cancel culture might judge their peers immoral for refusing to give up the music of canceled artists, even if they too are guilty of the same "moral lapse." Perhaps they excuse the ethical breach because the artist's music helped them through a hard time, or reminds them of a loved one. It's easy to view other people's behavior as evidence of major character flaws, because we aren't operating with all the context. Because cancel culture is binary, it often fails to consider context. Instead, it enables us to think more highly of ourselves by making harsh judgments of others based on their worst moments- and this does not only impact elites. Even ordinary people can be recorded during moments of crisis in public and subsequently shamed and even doxxed online. If "cancellation" signals the end of a person’s career or reputation based on their worst moment, then perhaps it is more vindictive than it is constructive. Ultimately, at the risk of sounding problematic myself, cancel culture is a form of public shaming that lacks nuance and complexity.

Confirmation Bias & Problematic Faves

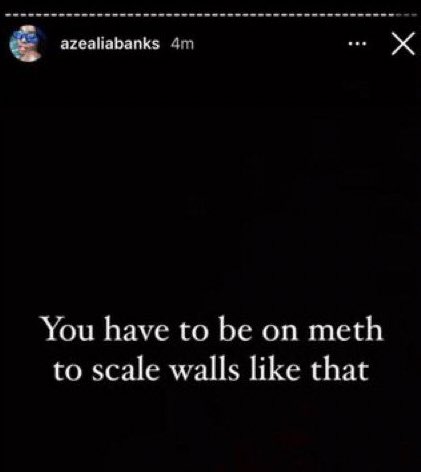

It can be all too easy to righteously hop on the hate train when our least favorite celeb is up for cancellation; however, most of us also have a soft spot for at least one “problematic fave." When rapper Azealia Banks announced that she sacrificed chickens in her closet for three years to achieve fame, I – as a fan, as a vegan, and as a (relatively) sane person – was appalled. Throughout her career, Banks has also started a string of messy feuds with other celebrities, including Kanye West, Lana Del Rey, Grimes and Elon Musk.

Though some of her tirades are amusing – such as her reaction to the January 6th Insurrection – I do not stand by Banks’s more offensive behavior. For example, she posted a two minute Instagram rant fat-shaming one of my all-time favorite singers. Regardless, I jump out of my seat to dance when her iconic track “212” comes on at my favorite bar.

Despite its best intentions, cancel culture is too easily misappropriated and weaponized to justify our biases. Our participation in cancel culture is often influenced by confirmation bias: we find evidence to support the beliefs and opinions we already hold about public figures. If we admire an artist’s music, we’re more willing to turn a blind eye to their wrongdoing– our existing positive attitude earns them a pass. If we dislike a musician, however, we are inclined to discuss their most cancelable qualities. We may even criticize them for the same behavior that we overlook in our problematic faves. For instance, critics of Taylor Swift often harp on the carbon emissions from her private jet – but what is the likelihood that all of our favorite artists fly commercial?

I suspect there is some overlap in the Venn diagram of "People Who Can’t Stand Taylor Swift" and "People Who Enjoy The Rolling Stones" – and guess what, folks? The Stones are flying private too. Swift’s carbon emissions are a convenient moral justification for existing negative attitudes toward her. As it stands, Swift's fans should not have to answer for her carbon emissions, because they are not responsible. Moreover, Swifties should not have to answer to critics who likely excuse the same behavior in their own problematic faves. It is okay to enjoy music by artists who live different lifestyles and make different choices than we do– yes, even if those choices are careless or immoral.

Music is an Art

Art appreciation is not based on social codes (or carbon emissions). It is based on the viewer’s – or in this case, listener’s – aesthetic experience, and individual experiences vary. Approach a painting in a gallery and appreciate its beauty – or don’t – but either way, it’s unlikely that the painter’s personal life influenced your perception. Similarly, a musician’s background may play little role in how a new listener engages with their work. Like a casual observer wandering through an art museum socializing, a listener may turn on a playlist while they are doing dishes. Others, like those who closely study the composition of each painting, may sit and listen to an album in its entirety, picking out elements that evoke genuine delight and wonder. The latter is an aesthetic experience, in which we engage with art or nature and seem to forget ourselves in a moment of beauty.

Psychologist Abraham Maslow (creator of Maslow’s Hierarchy) labeled these profound moments “peak experiences.” While a peak experience is difficult to put into words, Maslow prompted study participants to report “the most wonderful experience of your life; happiest moments, ecstatic moments, moments of rapture, perhaps from being in love, or listening to music.” Through his research, he concluded that the two easiest ways to elicit a peak experience are by having sex or listening to music (Maslow, 1968). Maslow’s research demonstrates the profound emotional impact that music has on us. It can be uplifting, sublime, epiphanic. It can resonate with us deeply. When music produces a peak experience which puts us in touch with the sublime, it becomes irreplaceable. Even if a creator is subsequently canceled, an awe-inspiring experience with their music is uniquely valuable to us.

Because music is linked with autobiographical memory, listening to it may also evoke a sense of nostalgia. In 2004, music psychologists Patrik N. Juslin and Petri Laukka used a questionnaire to study the emotional impact of music in our daily lives. For two weeks, they asked study participants to carry a tablet during all waking hours of the day. The tablets sounded an alarm seven times per day at random intervals, and each time, participants reported whether they were listening to music and completed a questionnaire about their emotional mindset. The researchers discovered that “Happiness and nostalgia were more frequent during musical emotion episodes than non-musical episodes. Conversely, negatively toned emotions, such as anger or anxiety, were more common during non-musical than musical emotion episodes” (Gabrielsson, 2010). During musical episodes, the five most frequently reported emotional states were: Happy, Relaxed, Calm, Moved, Nostalgic. The research validates what most of us may know instinctively: music has a positive effect on our emotional well-being.

Music-evoked nostalgia is particularly powerful because it “fulfills the existential function of self-continuity” (Routledge et al., 2011). Nostalgia reminds us who we are, where we have been, and how we have grown. It marks the passing of time, which helps strengthen our meaning of life. When we closely associate art with a cherished memory, it becomes irreplaceable. Though there is plenty of music in the world, we can’t realistically substitute just any music for music we hold dear– even if it is the "right" thing to do. We can’t edit our memories or replicate peak experiences with new, different, "appropriate" music just to comply with social expectations. Although we may feel ethically obligated to cast aside the work of canceled artists, this can deprive us of inspirational and sentimental moments which are singular and special and rare. Profound aesthetic experiences and music-evoked nostalgia reinforce the meaning of life itself; it is okay to want to hold on to that.

What About Serious Offenses?

Despite its flaws, I am grateful that cancel culture has played a role in holding sexual predators accountable for their actions. Most victims of sexual abuse privately carry shame, as if they – rather than their abusers – have transgressed in some way. The #MeToo Movement emboldened survivors to share their stories, find support, and place shame where it really belongs: with the offenders. #MeToo showed abusers in high places that they are not above the law. Ever since, conscientious listeners have been faced with an ethical dilemma: What do we do when our favorite musicians are accused of sexual misconduct? Does streaming their music, potentially funding their legal defense expenses, reinforce the idea that they are untouchable?

In what is perhaps the most extreme example, R&B singer R. Kelly was sentenced to 30 years in prison for sex trafficking and racketeering in 2022 (though his systematic abuse of young women dates back to the 1990s). In 1994, R Kelly married 15 year-old singer Aaliyah while he was 27 years old– after helping produce her debut album Age Ain’t Nothin’ But A Number. The album title, paired with rumors of marriage to a minor, would certainly arouse vitriol post- #MeToo. In 1995 however, the marriage rumor was casually reported in The Michigan Daily. Perhaps such nonchalant attitudes are what made Kelly think he was untouchable; he even brazenly sang about sex trafficking during a show in Ethiopia, asking the audience “Do you have your passport? Did you get your shots? Girl, would you like to come back with Rob to America?”

Since his conviction, it’s difficult to overlook the suspicious themes in his work. R Kelly’s discography is so heavily laden with sexual innuendo that it can be difficult to compartmentalize appreciation for his music and disapproval for his behavior. When a musician's work is thematically entwined with their wrongdoing or their identity, it can pollute our listening experience and overpower our existing positive associations. In such cases, we may genuinely want to stop listening.

When listeners appreciate music for its meaning and aesthetic value independent of the artist, we have an easier time compartmentalizing. R. Kelly's inspirational track "I Believe I Can Fly" makes no reference to his identity or sexual proclivities. Upon the song's release, an Associated Press review commented on its "gospel-styling," saying "hearing R. Kelly's booming voice reach a crescendo while backed up by a choir is a rousing performance that will get many replays." The song is emotionally evocative, and has likely elicited some peak experiences. It delivers a simple, universal message of hope, and has been performed by gospel choirs in black churches. It was also featured in the 1996 children's movie Space Jam, making it an understandable source of nostalgia for 90s kids. For better or worse, the song is weaved into personal and cultural histories and has developed unique meanings in listeners' lives. As controversial as this may sound, the same can be said of his more sexually explicit work. Nostalgia is a powerful force, perhaps strong enough for some listeners to reflect primarily on their own positive memories while hearing an R. Kelly song, rather than on the disturbing new context to his suggestive lyrics. Studies show that "Music that was popular during an individual's youth, and thus likely nostalgic, shapes one's lifelong musical preferences" (Holbrook, 1993). Knowing that the music of our youth has a lifelong impact, it's entirely possible that its sentimental value could make us overlook questionable lyrics.

Still, R. Kelly's crimes make carbon emissions and celebrity feuds look like petty concerns. R. Kelly has not been unfairly judged- his decades of abusive behavior are very legitimate cause for cancellation. In 2017, Atlanta activists Kenyette Tisha Barnes and Oronike Odeleye started the #MuteRKelly Movement in an effort to cancel his concerts and remove his music from radio-play in Atlanta. Though R. Kelly's music remained available on Spotify, in 2019 the streaming service gave users the permissions to “mute” R. Kelly’s work by selecting "Do not play this artist." A main objective of the #MuteRKelly Movement was to limit the R&B singer's financial income. Consequently, his continued listeners are often criticized for "buying his product." As it stands, the general public struggles to forego unethical products. For example, Nestle has long profited from slave labor on cocoa farms in Africa's Ivory Coast. Though Nestle owns Gerber Products Company, it'd be a little reductive to accuse parents who buy Gerber baby food of supporting slave labor. Besides, as demonstrated, music is more than just a product to us; it is a source of inspiration and nostalgia. Some principled listeners may choose to pirate the music of problematic artists to avoid lining their pockets. While I commend their efforts, streaming the music of problematic artists is as cancelable as buying Gerber baby food- it isn't.

Perhaps it's especially taboo to support R. Kelly's work because we watched his trial play out in real time. In her book Why It’s OK To Enjoy The Work of Immoral Artists, Mary Beth Willard writes:

"Sometimes it seems easy psychologically for us to separate art from the artist, especially when their life and work resides in the distant past. Many historically great artists were horrible people, and in a lot of these cases, we view their misdeeds as nothing more than a historical footnote."

David Bowie and Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page both committed statutory rape in the 1970s, yet their listeners are rarely considered complicit. This ethical inconsistency could be a result of recency bias - R. Kelly's wrongdoing is more fresh in our minds. It could also be due to shifting cultural attitudes around sex and consent. Today, we are living in a post- #MeToo world, whereas some contextualize Bowie and Page's behavior by the "free-love" culture of the '70s. Groupie Lori Mattox was fifteen years old when she lost her virginity to Bowie, and although she remembers the experience fondly, Bowie's actions are no less appalling: she was a child. Perhaps cancel culture hasn't come for David Bowie because he is not alive to profit from continued streaming. On the other hand, guitarist Jimmy Page is still alive and his fans seem to escape criticism for listening to Led Zeppelin.

Each of these three musicians has engaged in indefensible acts, yet R. Kelly's listeners are more heavily policed, indicating additional bias within cancel culture. It's hardly fair to accuse R. Kelly's listeners of supporting abuse when fans of other problematic musicians arbitrarily get off scot free. The truth is, most people do stream the work of problematic artists- and that is okay. The conversation should be about the musicians' wrongdoing, because avoiding the work of every canceled artist is a non-starter.

Big List of Problematic Affirmations

Listeners should not feel obligated to deny ourselves valuable experiences to comply with punishing social codes. If an artist's wrongdoing causes enough distress to genuinely damage our listening experience, of course we should stop listening. If an artist's music makes us feel Happy, Relaxed, Calm, Moved, or Nostalgic, then we should permit ourselves the joy of listening. Cancel culture does not erase our fond memories, and that is okay. Cancel culture does not dictate our artistic preferences, and that is okay. We do not have to justify our reception to artwork. Our experiences with art belong to us.

Check Out Work by Some of my Problematic Faves Below: